JVM Typed Functions

Previously on haxe.org

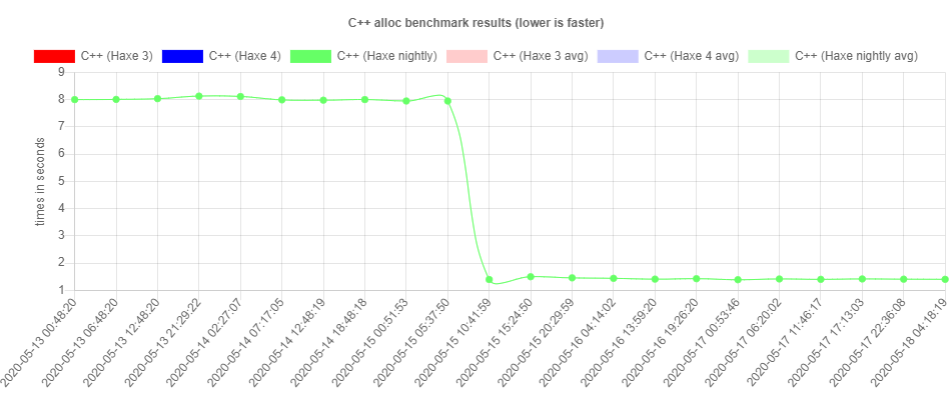

It's been about a week since I've announced the Haxe 4.1.0 release and made the bold claim that the JVM target went from being experimental to being the fastest Haxe target. Just as planned, this got the attention of various people, among which was Hugh. He flipped some switch in hxcpp and this happened:

I'll give the disclaimer that this is just a benchmark and not indicative of real performance improvements. Hugh himself told me that this particular benchmark was pathological for hxcpp due to garbage collection specifics. Nevertheless, any improvement helps and I'll happily abuse graphs like this for marketing purposes! So: "Allocations on hxcpp are 5x faster now! Haxe is amazing!"

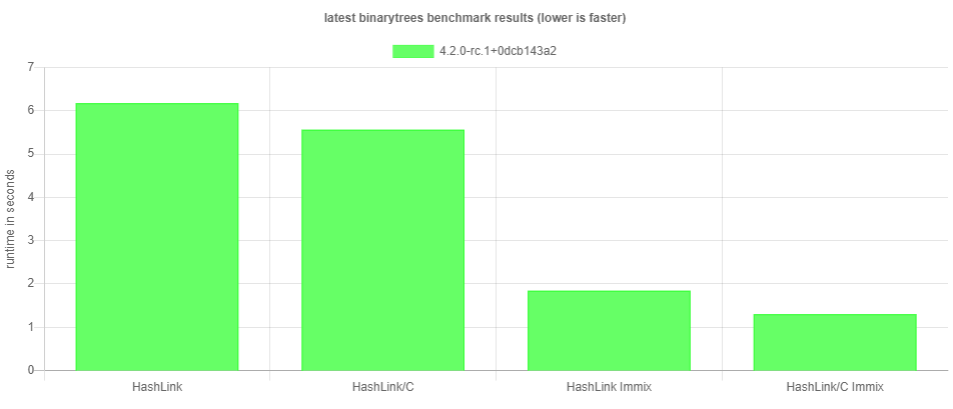

Speaking of things being faster, after my last post we got some questions about what that HashLink Immix thing was about. It's a new garbage collection implementation which Aurel Bily, formerly known as Aurel Bily the Intern, is currently working on. He gives some information about it in this post. Naturally, I have a benchmark graph to tout:

In summary, the optimization game is on and I look forward to future developments in that regard. We will also make an effort to not only pay attention to our "pet targets", but also the more obscure ones, like the JavaScript target. Ah, I'm joking! JavaScript does very well in the benchmarks. Feel free to check it out, and please let us know if you have a suggestion for more benchmarks.

JVM Typed Functions

Now for what I actually want to talk about today. At least one person on reddit was interested in what we changed to improve the performance of anonymous functions and closures, so I'm happy to go into detail. First of all, let's establish some context of what we're actually talking about here:

function callMe(f:Int->Void) { f(12); } function main() { callMe(value -> trace(value)); }

(Note that I'm using module-level statics for these examples to reduce some noise. That's right, thanks to nadako's work we now got support for that on our development branch! If you're interested, grab a nightly build and check it out!)

The important part here is that with the f(12) call, we don't know what exactly we are calling. It could be a static function, or a method closure on some instance, or an anonymous function, or perhaps something else. Even worse, we don't necessarily know the exact signature of what we're calling. The call-site thinks that it's a function which accept a single argument of type Int and returns nothing. However, Haxe's type system allows assigning functions with a different type to this:

// broader argument type callMe((value:Float) -> trace(value)); // broadest argument type callMe((value:Dynamic) -> trace(value)); // non-Void return type callMe(function(value:Dynamic) return "foo");

Any call in the JVM run-time needs an exact type at bytecode-level. This is encoded as something called a descriptor. As an example, the Int -> Void function from the example would have a (I)V descriptor. We can verify this by looking at the decompiled bytecode of the callMe function:

public static callMe(Lhaxe/jvm/Function;)V L0 LINENUMBER 2 L0 ALOAD 0 BIPUSH 12 INVOKEVIRTUAL haxe/jvm/Function.invoke (I)V RETURN

Don't worry if you aren't familiar with bytecode instructions. The main point here is that we have to call something that actually has the (I)V descriptor. In our case, that something is the method invoke on the class haxe.jvm.Function.

haxe.jvm.Function

The base class for all typed functions is haxe.jvm.Function. It utilizes information collected during compilation by generating a whole bunch of invoke methods, which call other invoke methods. This is done by classifying types as one of 9 possible classifications:

type signature_classification = | CBool | CByte | CChar | CShort | CInt | CLong | CFloat | CDouble | CObject

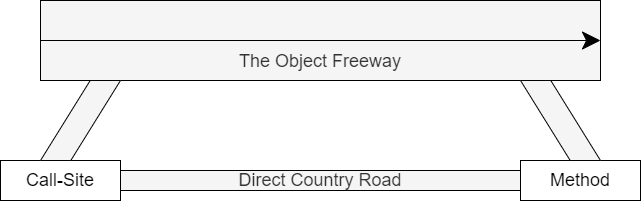

We can visualize the relation between these methods like a freeway with an on-ramp and an exit:

Ideally, we would always take the direct country road from the call-site to the method implementation. Unfortunately, that road can sometimes be a bit bumpy and our vehicle might not be equipped with appropriate tires (= types). This then requires us to take the Object Freeway, and find the exit ramp to our method. The Object Freeway consists of invoke methods that take any number of java.lang.Object arguments and also return java.lang.Object.

The on-ramp

The on-ramp is implemented directly in haxe.jvm.Function like so:

- We start with the concrete argument types, classified as per the classification mentioned above.

- If any of these argument types is not

CObject, call theinvokemethod with the same number of arguments where all argument types have been replaced withjava.lang.Object. - Next, if our return type is not

CObject, call theinvokemethod with the same argument types where the return type has been replaced withjava.lang.Object.

The last invoke method is part of the freeway: It is a method with a given number of java.lang.Object arguments and a return type of java.lang.Object.

The Object Freeway itself

In order to support optional arguments, the implementation has to make room for the possibility that a given call-site might not provide enough arguments to satisfy a given method descriptor. This becomes particularly relevant when working with Reflect.callMethod, where users commonly expect that optional arguments can be omitted.

Default values in Haxe are not part of the call-site, but are implemented in the functions itself by checking something along the lines of if (arg == null) arg = defaultValue. This has some advantages and disadvantages. A big advantage is that this can work even for call-sites that don't know what they are calling, such as Reflect.callMethod. The only problem is that the call has to make sure that there are enough arguments. The compiler itself does that by appending null values to the argument list, so dynamic call-sites have to do something similar.

This is achieved through the next step in our invoke quest chain: If the arity (number of arguments) is less than the maximum assumed arity X, call the invoke method that has an additional argument of type java.lang.Object and use null as the value. The number X is determined at compile-time by keeping track of the method that has the most arguments. These calls move us along the Object Freeway until we find an exit.

Here's how the Object Freeway parts of haxe.jvm.Function look in the decompiled code for our small example:

public Object invoke() { return this.invoke((Object)null); } public Object invoke(Object arg0) { return this.invoke(arg0, (Object)null); } public Object invoke(Object arg0, Object arg1) { return null; }

The exit

So far, all invoke methods were part of the base class haxe.jvm.Function. We can get on the freeway, but we cannot leave it yet. The exit itself has to be implemented on our concrete method objects. Fortunately, this is quite straightforward: All we have to do is implement the invoke method with the correct number of java.lang.Object arguments and a java.lang.Object return type. That method will then, through normal override resolution, be picked up once it is reached on the freeway. Of course it then has to de-objectify the arguments in order to call the real implementation.

Here is an example using a local function:

function callMe(f:Int->Void) { f(12); } function main() { function f(value:Int) { trace(value); } callMe(f); }

The local function f is generated like this:

public static class Closure_main_0 extends Function { public static Main_Statics_.Closure_main_0 Main_Statics_$Closure_main_0 = new Main_Statics_.Closure_main_0(); Closure_main_0() { } public void invoke(int value) { Log.trace.invoke(value, new Anon0("_Main.Main_Statics_", "source/Main.hx", 7, "main")); } public void invoke(java.lang.Object arg0) { this.invoke(Jvm.toInt(arg0)); } public java.lang.Object invoke(java.lang.Object arg0) { this.invoke(arg0); return null; } }

The bottommost invoke method is the one on the freeway and starts our exit ramp. It invokes the invoke method above it, which has a void return type (note that this looks like a self-call in the decompiled code, but the actual bytecode has a different descriptor (Ljava/lang/Object;)V). Finally, that one then invokes our concrete implementation, which has our original types.

As mentioned initially, the bytecode at the call-site is INVOKEVIRTUAL haxe/jvm/Function.invoke (I)V. This matches the descriptor of our concrete implementation invoke method, which means that the actual call can be made without any overhead (that's the country road). In contrast, if the argument types were different, we would detour over the Object Freeway and eventually reach the concrete implementation, too. This way, we have a fast track for sanely typed code and a slower track for insanely typed code.

Native closures and calls with unknown arity

Reflect.callMethod

Our examples so far always knew the number of arguments and could generate invoke calls accordingly. When using the aforementioned Reflect.callMethod function, we have to dispatch to the correct invoke method depending on the number of arguments provided. This is generated exactly as dumb as it sounds and is also part of haxe.jvm.Function:

public Object invokeDynamic(Object[] args) { switch(args.length) { case 0: return this.invoke(); case 1: return this.invoke(args[0]); default: throw new IllegalArgumentException(); } }

The number of cases depends on the maximum determined arity mentioned before. This is crude, but effective.

Native closures

Finally, we have to deal with actual run-time closures in some way. This refers to cases where the compiler doesn't know that a closure of a field is taken, which can happen through the reflection API or liberal usage of the Dynamic type. In cases like this we have to tie our elaborate haxe.jvm.Function framework together with the reflection information we get from Java itself, which is mostly about java.lang.reflect.Method.

This is handled by haxe.jvm.Closure which carries an instance of java.lang.reflect.Method and an optional context typed as java.lang.Object. The just mentioned invokeDynamic method is compatible with Method.invoke, which is what we want to call. To that end, Closure overrides invokeDynamic in order to make that call. This requires some more work regarding function arguments, but that is uninteresting in the scope of this discussion.

That's already enough to support calls through Reflect.callMethod as those invoke invokeDynamic. However, as we demonstrated initially, our properly typed call-sites actually emit concrete invoke calls. In order to connect those to invokeDynamic, Closure extends a generated class ClosureDispatch which simply re-routes these calls:

public class ClosureDispatch extends Function { public ClosureDispatch() { } public Object invoke() { return this.invokeDynamic(new Object[0]); } public Object invoke(Object arg0) { return this.invokeDynamic(new Object[]{arg0}); } public Object invoke(Object arg0, Object arg1) { return this.invokeDynamic(new Object[]{arg0, arg1}); } }

Closing remarks

This approach is certainly not going to win any Java awards for exceptional elegance, but I won't get tired of mentioning how efficient it is. It is very nice to reward properly typed code with good performance while still supporting all the dark arts of dynamic typing and reflection. It might be possible to improve this further, too:

- Usage of the Object Freeway requires boxing of basic types. In theory, there could also be a Double Freeway to avoid that. However, it is unclear if there are scenarios where this could actually be relevant and significant.

- I'm not sure how well native interoperability works with all this. We briefly discussed the idea of providing one interface per invoke-signature, which is what some other Java generators do. The problem here is that we need a common base class in the API anyway, so the advantage of juggling individual interfaces over just extending

haxe.jvm.Functionand implementing your favoriteinvokemethod seems dubious. - Another idea was to automatically implement some java functional interfaces. In fact, I got started with that out of curiosity and then completely forgot about it. As of Haxe 4.1.0, only the interfaces for

ConsumerandBiConsumerare inferred automatically. It remains to be seen if this has any value.

Please let us know if you have any questions or comments!